At the beginning of the eighteenth century, South Carolina’s colonial government raised a fortified trace of earthen walls and moats around the nucleus of urban Charleston. These defensive works constrained the town’s growth for more than twenty years, but then quietly vanished before a burst of civic expansion in the mid-1730s. Questions of when and why the earthworks were dismantled have baffled generations of historians and inspired competing theories. In today’s program, we’ll unpack the forgotten story of government neglect that gradually reduced the “Walled City” during the late 1720s.

Over the past several years, I’ve crafted a number of podcast essays about Charleston’s early fortifications. My goal has been to explain not only the chronology of the urban fortifications, but also the broader historical context that defined their rise and fall. The principal source for this information is the extant manuscript journals of South Carolina’s provincial government, augmented by related government documents, which I’ve examined in numerous visits to the South Carolina Department of Archives and History in Columbia over the last two decades. As I described in Episode No. 230, for example, records created during the early years of the eighteenth century provide a relatively clear picture of when and why civic leaders decided to enclose the colonial capital within a network of walls surrounded by a moat: Fear of an imminent Spanish attack in late 1703 inspired the provincial government to appropriate funds for the rapid construction of the Charleston enceinte—a fortified enclosure—which was effectively completed by the end of 1704.

Similarly, government records created over the ensuing three decades contain numerous references to the repair and maintenance of the brick curtain wall along the east side of East Bay Street and the earthen walls enclosing the south, north, and west sides of Charleston. The extant documents might not contain as many details as we’d like to see, but they represent a nearly-continuous paper trail for tracing the evolution of the town’s early fortifications.

Reading through South Carolina’s legislative journals of the 1720s and early 1730s for the first time, I expected to find the text of a discussion regarding the fate of Charleston’s earthen walls. The provincial government used tax revenue to build and maintain the enceinte surrounding the capital, so I imagined that its removal would require some act of government, like a resolution, ordinance, or statute. I found no such discussion, however, nor any sort of act or decree that might have triggered the demolition of the public earthworks. By the time I reached the legislative journals of the mid-1730s, I found discussions of extending Church Street, Dock Street, Bay Street, Tradd Street, and Broad Street beyond the boundaries of the fortifications created thirty years earlier. The earthen walls were evidently gone by 1733, but I found no explanation of how or when they disappeared.

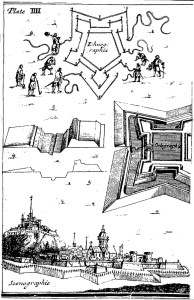

Detail from the 1739 ‘Ichnography of Charles Town at High Water,’ showing the outline of the former “enceinte” created in 1704.

Turning to secondary sources for help, I discovered that no historical text published in the past three centuries offered a reliable answer to the puzzle of Charleston’s disappearing fortifications. In fact, some observers living in the eighteenth century published inaccurate solutions to the question. For example, the well-known map printed in London in 1739, titled “The Ichnography of Charles-Town at High Water,” depicts the outline of the fortified walls that formerly constrained the south, north, and west sides of the town. A caption printed in the lower left corner of the map states that “the double lines represent the enceinte as fortified by the inhabitants for their defence against the French[,] Spaniards & Indians[;] without it were only a few houses & these not thought safe till after the signal defeat of ye Indians in the year 1717, at which time the north west & south sides were dismantled & demolished to enlarge the town.” That text is definitely inaccurate, however, because extant legislative records demonstrate South Carolina’s provincial government maintained the earthen fortifications of Charleston for several years beyond 1717.

Another brief statement about the removal of Charleston’s earthen fortifications appears within an essay about defending South Carolina, published in the Gentleman’s Magazine of London in 1745: “In Queen Anne’s war [1702–13], this place was strengthened by tolerable works on the land side, which were razed by General Nicholson, when governor, to oblige some of his particular friends.” Francis Nicholson (1655–1728) was appointed governor of South Carolina the autumn of 1720 and held that title until his death in March 1728, but he actually resided in Charleston between May 1721 and May 1725. The essay published twenty years later implies that Nicholson was somehow responsible for demolishing the earthworks in the mid-1720s, either by executive decree or by steering the provincial legislature towards that end. The extant government papers from that period do not support this theory, however, although Governor Nicholson was certainly involved in the process.

Over the past decade, I’ve re-read the extant legislative journals of the 1720s multiple times and combed archives in London searching for obscure records that might illuminate this history mystery. The answer, it turns out, was embedded in the legislative journals of the mid-1720s that I initially consulted. It did not leap off the page, but it came into focus after I revisited the clues and considered the broader context. Charleston’s first earthen walls faded out of existence over a period of several years, and the facts related to their disappearance form a rather complex narrative. For the first time in three hundred years, the real story can now be told.

This story continues at Charleston Time Machine. . . .